When your baby is born, the first thing a doctor, midwife, or nurse does is a quick examination to determine his or her Apgar score. An Apgar score is a rapid way to evaluate your baby’s physical condition and determine if there is any need for immediate extra medical attention or emergency care.

Your baby’s Apgar score is taken at one minute after birth and again at five minutes after birth. The doctor, midwife, or nurse examines your baby and assigns a score of 0, 1, or 2 points for each of five aspects of his or her health and appearance. These are:

- breathing

- heart rate

- muscle tone

- reflexes

- skin color

The higher the Apgar score, the better the baby is doing at weathering his or her birth and first few minutes outside the womb. A perfect score is 10, but a normal score is 7 or above. Babies often have a lower score at the one minute mark and improve by five minutes. Babies born by cesarean section or after a difficult birth often have a lower one-minute score. A baby with a low Apgar score may need a little oxygen orneed to have his or her nose cleared out so that they can breathe better. Some need a little physical stimulation to bring their heart rate up.

An Apgar score is a quick and useful way of determining a baby’s condition right after birth. It does not predict a baby’s long-term health or any future physical problems.

APGAR is often used as a memory aid for the five aspects of the test: Appearance (color), Pulse, Grimace (reflexes), Activity (muscle tone), and Respiration (breathing). But this is not an acronym, but a “backronym,” where words were chosen to fit the name. Apgar was the last name of an amazing woman.

The Apgar test and score was created by Virginia Apgar, MD, an anesthesiologist, who helped create the field of obstetrical anesthesia. When Dr. Apgar graduated from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, she wanted to be a surgeon, but was advised to go into anesthesiology, which was then practiced primarily by nurses. Her advisor, George Whipple, MD, was not being sexist; he thought that she was the person who could best advance the fledgling field of anesthesiology.

Dr. Apgar studied anesthesiology and became the first director of the Division of Anesthesia at Presbyterian Hospital and the first woman to be a full professor at Columbia. She was known there as an exceptional teacher.

She was especially interested in the effects of anesthesia on woman in labor and on babies. At that time, there was no uniform way to determine how healthy a baby was at birth.

The Apgar Score, as it later became known, had its origins in a medical resident’s question: How would one do a standard, rapid assessment of a newborn’s condition? Apgar responded, “That’s easy, you would do it like this.” Grabbing the nearest piece of paper, she jotted down five objective points to check.

Dr. Apgar refined the test and published her research on the test in 1953. The Apgar test slowly gained a following. In 1961, a medical resident in Colorado came up with the “backronym” for the Apgar score, which delighted Dr. Apgar. The backronym was widely adopted, to the point that some people did not realize that Apgar was a person and were surprised to be introduced to her.

Virginia Apgar never married, but she was an active woman known for gardening, playing golf, stamp collecting, and having an earthy sense of humor. An avid musician, she usually traveled with her violin and later in life built two violins, a viola, and a cello. She started taking flying lessons when she was in her fifties because she said she wanted to fly a plane under the George Washington Bridge.

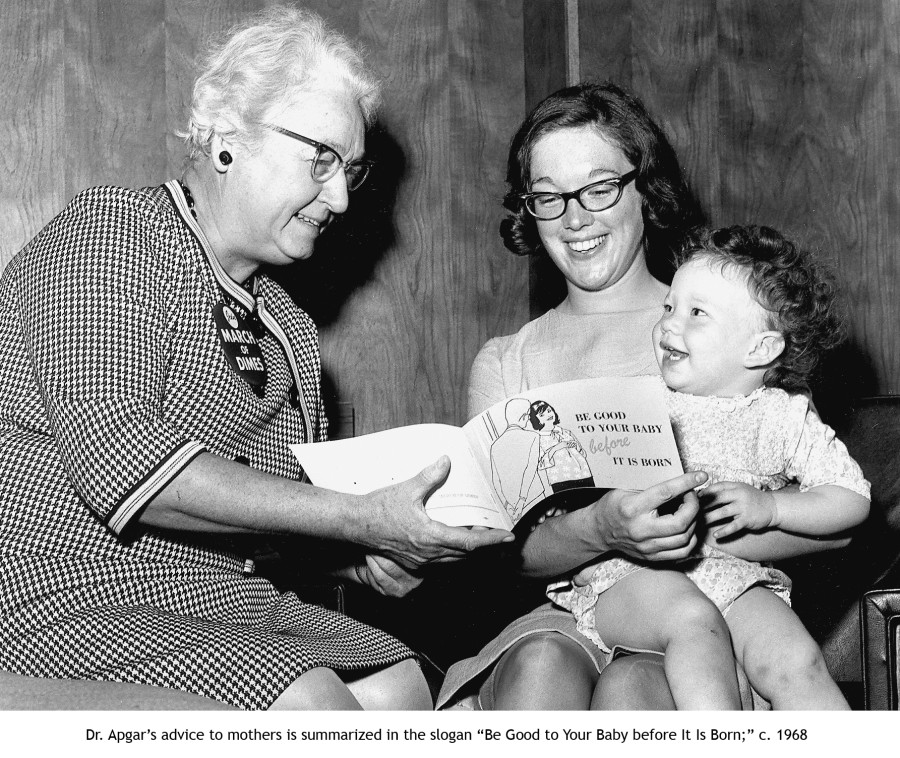

Creating a test that is used worldwide would be enough for most people, but Virginia Apgar went on to have a second career as a researcher into the causes of birth defects. She was approached in 1959 by what was then the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis-March of Dimes to become the head of its new division on birth defects. She served the March of Dimes as Director of Basic Medical Research and later Vice-President for Medical Affairs, and still had time to teach at Cornell University School of Medicine.

Virginia Apgar developed liver disease in her early sixties and died at age 65 in 1974. She has been honored with a U.S. postage stamp in 1994 and inducted into the National Woman’s Hall of Fame in 1995.

“It has been said that every baby born in a modern hospital anywhere in the world is looked at first through the eyes of Dr. Virginia Apgar.”